Miljenko Jergović: Josip Lovrenović, matična ploča

(Predgovor katalogu izložbe grafika i fotografija Josipa Lovrenovića „XII, Session, Mramorovi“, održane u GS-Tvornici mašina Travnik u Docu kod Travnika, početkom svibnja 2017. godine) Sve što Josip Lovrenović izlaže na ovoj izložbi, s proljeća 2017. u srednjoj Bosni, za temu ima sjećanje. Iako, isto bi se moglo reći za bilo čiju izložbu, bilo čega. Sve što se da izložiti, od razodjevenih konfekcijskih lutki u izlogu na glavnoj sarajevskoj ulici travnja 1992, do crteža Nives Kavurić-Kurtović, u Galeriji Klovićevi dvori u Zagrebu lipnja 2016, i još sve ono što je između toga, saksije s kadificama u prozoru jednokatnice, petolitarska tegla sa zaslađenom vodom i ružinim laticama na osunčanom prozoru petoga kata, sve je to, u trenutku kada se izloži, sjećanje. Čovjek ne može o sebi ništa reći što već nije sjećanje. Samo što sjećanja ima osviještenih i neosviještenih, namjernih i nenamjernih. Postoje i ranjena sjećanja: to su ona sjećanja koja nisu izjedena anarhoidnom, ali ipak sustavnom i smislenom snagom zaborava, nego su stradala djelovanjem neke od velikih nepogoda čovjeka i čovječanstva. Dvije najveće nepogode sjećanja su rat i senilnost. Ova druga danas ima modernije ime: Alzheimerova bolest. Rat je Alzheimerova bolest jedne civilizacije. Ono čega se zajednica prisjeti kad nastupi mir nije sjećanje, nego njegov nadomjestak, surogat sjećanja. Poslijeratna vremena su obilježena dugim i mahom uzaludnim pokušajima da se nanovo uspostavi kontinuitet sjećanja. Zato su u poslijeratna vremena pisci, slikari, redatelji, glumci tako živi, aktivni i plodni. Oni stvaraju fikciju koja igra ulogu sjećanja. Hašekov Dobri vojnik Švejk, Renoireova Velika iluzija, Kod nas u Auschwitzu Tadeusza Borowskog zamijenili su sjećanja generacija postradalih i poludjelih, ali su, što je možda i važnije, omogućili „postmemorijska sjećanja”, sjećanja preko groba. Josip Lovrenović jedan je od poslijeratnih umjetnika. Tako bi trebalo pisati u njegovoj umjetničkog legitimaciji, na njegovoj posjetnici, u najavi ove izložbe… Iako tu nigdje nema prizora s fronta, nema ni opkoljenog grada, masovnih grobnica, njihovih i naših genocida, naših mučeništava a njihovih krvništava, niti sve one poslijeratne bižuterije kojom preživjeli ukrašavaju svoje prazne grobove, rat je središnje mjesto u njegovu sjećanju. Ili, tačnije rečeno, središnja praznina. Tu prazninu valja ispuniti vrlo preciznim - ali time ništa manje uzaludnim - gotovo forenzičkim pokušajem rekonstrukcije izgubljenog svijeta. U svome diplomskom grafičkom ciklusu od dvanaest listova u dvanaest mapa Lovrenović je tehnikom akvatinte, s doradama, prenosio tipske prizore i znakove sa stećaka, kombinirajući ih s predmetima svakodnevne upotrebe kojima se u protoku vremena izgubila svrha. Tu se nije radilo o osobnom sjećanju, niti o zloduhu kolektivnog ili, ne daj Bože, nacionalnog sjećanja - nacija i sjećanje su u vječnoj kontradikciji - nego o sjećanju na sjećanje. Stećci nisu spremnici zajedničke memorije, ili memorije svijeta, kao što bi voljeli reći nacionalni ili multinacionalni fantasti. Prije bi ih se moglo doživjeti i tumačiti spomenicima zaborava. Ne zna se tko pod njima leži, a vizualne, simboličke poruke na njima su protokom vremena i silom zaborava od vrlo konkretnih, svakodnevnim jezikom sastavljenih izvještaja o minulom životu, postali visokostilizirane vizualne i tekstualne metafore. Kao što su se u svojevrsne metafore pretvorili i alati za koje više nitko ne zna čemu služe. Metaforizacija putem zaborava, ili pretvaranje zbiljskoga svijeta procesom zaboravljanja u metaforu i u znak, samo je po sebi velika tema. U tome je i pripovijest o stećcima, onako kako ih Lovrenović predstavlja. Godinama kasnije, 2005. u Varšavi, na specijalističkim studijima, nastaje ciklus Session. Dvanaest (opet dvanaest) grafičkih listova monumentalnog formata - najvećega koji je mogao biti tehnički izveden, spojeni čine jednu memorijsku cjelinu. U radu su korištene one obiteljske fotografije koje su slučajno sačuvane tokom ratnih pustošenja, progonstava i nevoljnih selidbi, tako što čine fragment, vizualni i sadržajni, značenjski, unutar šire cjeline jednoga grafičkog lista, koji opet, s preostalih jedanaest čini onu još širu, iako ne i konačnu, cjelinu rada. Session je impresivno djelo, jer demonstrira dva suprotna i suprotstavljena principa stvaranja. Istovremeno, radi se o snažnim, krajnje intimističkim grafičkim minijaturama i o svojevrsnoj grafičkoj freski ili, bolje, ikonostasu. Session jedan je mogući ikonostas sjećanja. Fotografije što ih je Lovrenović koristio u Sessionu uglavnom su snimane u ona vremena kada je čin fotografiranja podrazumijevao svojevrsni ceremonijal. Budući slikani bi se postrojili ispred objektiva iza kojeg je stajao fotograf - svojevrsni gospodar sjećanja - profesionalac, a tek iza Drugoga svjetskog rata plemeniti diletant - amater kako je moderno reći - i u kratkoj bi izmjeni pogleda, fiksiranju izraza lica, grimasa i gesti, bila ulovljena vječnost. Ili bi, tačnije rečeno, u munjevitom osvjetljenju vječnoga mraka fotografskog filma bila ulovljena smrt. Fotografiranje je svojevrsna vježba za smrtni čas. Takav si na toj slici kakav nikada više nećeš biti. I nikada više nećeš biti. Većinu ljudi s tih upotrijebljenih fotografija umjetnik ne poznaje. Oni su zaboravljeni, ispali su iz sjećanja, pretvorili se u anonimne svjedoke, u likove i znakove sa stećaka. Poznati su mu tek oni s kojima čini jedno zajedničko generacijsko sjećanje - dakle, otac, majka, djed, baka, možda i pradjed, ako se pradjedovog lika još netko u kući sjeća. Sva čovjekova povijest, obiteljska povijest, a u velikoj mjeri i sva povijest čovječanstva može stati u sjećanja tri generacije: sina, oca i majke, baka i djedova. Odlaskom najstarije generacije iščezava cjelokupno njezino sjećanje. Ostaju samo fragmenti, pretvoreni u predaju, legendu i mit, nepouzdani i prazni. I tako iz stoljeća u stoljeće, povijest obuhvaća između sedamdeset i stodvadeset godina, koliko traju naša i sjećanja naših bližnjih, te njihova sjećanja na sjećanja. Josip Lovrenović bilježi taj proces, i bilježi sebe unutar tog procesa. Obiteljska povijest njegova je autobiografija. Koristeći fotografije u grafičkom procesu on ih, i mimo vlastite namjere, rekodira, preobražava i pretvara u nešto drugo, kako u vizualnom, tako i u sadržajnom smislu. Ono što je do maloprije bila fotografija, sada je trag na grafičkoj ploči, crtež koji teži apstrakciji, i na kraju - apstrakcija i ništa. Tako jednom snimljena slika prelazi put od vjerne i konkretne slike jednoga svijeta do znaka, simbola, amblema. Riječ je o istom onom putu koji su tokom stoljeća prešli simboli i znakovi sa stećaka. I oni su, u vrlo određenom smislu, jednom jako davno bili - fotografija. U Srednjemu vijeku se za tačniju i istinitiju fotografiju naprosto nije znalo. A naša je iluzija da se od stećaka do digitalne slike na fotoaparatu išta bitno promijenilo. I dalje smo sami sa svojim sjećanjima, i s tri generacije memorijskih svjedoka nakon kojih slijedi zaborav, brisanje ploče, praznina. Session je, u biti, nedovršeni rad. Ikonostas jedne osobne memorije, jednoga ljudskog sjećanja, komponiran od dvanaest fragmenata. U Varšavi 2005. postavljena je osnova, matična ploča, koja se može beskonačno nadograđivati, mijenjati i brisati. Potencijalno, riječ je o cjeloživotnom procesu, čije je trajanje ograničeno isključivo čovjekovim sjećanjem, a potom i odnosom sjećanja i zaborava. U grafičku ploču sjećanje će ugrebati, upisati, razjesti nove elemente, lica, oblike i predjele, koji će se djelovanjem zaborava pretvoriti u znakove i simbole. U nastojanju da definira ratnu traumu Aleida Assmann, njemačka kulturologinja i povjesničarka književnosti, ovako sublimira nalaz kliničke psihologije s kraja dvadesetog stoljeća: „Sjećanje koje ne nalazi put do svijesti upisuje se u tijelo.” U posljednjih pola stoljeća, možda i duže, među običnim je svijetom, u svakodnevnom komuniciranju, ustaljeno vjerovanje da su brojne fizičke bolesti izazvane psihičkom traumom, a onda i ratom kao traumom svih trauma. Ali ne mora se aforistično koncizan zaključak o tijelu i sjećanju nužno odnositi na bolesti tijela. I umjetnost je, na kraju krajeva, trauma koja se upisala u tijelo, divlje meso, tumor na duši i memoriji. Fotografije stećaka naizgled su konvencionalniji dio ove izložbe. U crno-bijeloj tehnici, snimane u maniri Toše Dabca, koji je već prije šezdesetak godina izradio kanoniziranu panoramu svijeta stećaka, ove fotografije predstavljaju golo „stanje stvari”. Lovrenović se ne bavi naknadnim metaforiziranjem svojih kamenova, donosi ih onakve kakvi jesu, ne upisujući u njih ni vlastito iskustvo, ni iskustvo svoje epohe. On ne čini ništa od onoga što je danas u modi, ne nacionalizira stećke, ne čini ih bosanskijim ni svjetskijim nego što sami po sebi jesu, ne rasteže po stećcima vlastitu poetsku žicu, niti ih svodi na naivno-poučni svijet bajki na srednjovjekovne teme, s dobrim Bošnjaninom i zemljom plemenitom kao središnjim motivima. Fotografira ih onakve kakvi jesu, slobodne od ljudi i od života, ali, u najvećoj mjeri, slobodne od vremena koje ih troši, glača i sasipa u prah. Stećci u Lovrenovićevom radu imaju dvojaku ulogu. Kao skladišnici zaborava, čuvari memorije koja je davno postala ničija, stećci su ono što će jednom postati obiteljske fotografije. Stećci su slike iščezlih obitelji. S druge strane, iako je za razliku od nje trodimenzionalan, stećak je neka vrsta grafičke ploče. U njega je uklesano, ugrebano, upisano ono što bi jednoga dana voljom nekoga svemoćnog nebeskog tiskara, u štampariji za sve formate, moglo biti otisnuto na papir. Nije to Lovrenovićevo otkriće, znali su to grafičari prije njega, stećak je prapočelo umjetnosti multioriginala. Lice stećka žudi da bude odštampano. Ova izložba ima dobro i tačno mjesto. Istinito mjesto. Osim što su Dolac i Travnik mitska mjesta bosanske priče, bosanskog narativa, umjetničkog koliko i povijesnog, Tvornica mašina i štamparija u sebi nose značenja i simboliku istovremeno bliske Lovrenovićevoj strategiji sjećanja i njegovom beskrajnom i doživotnom Sessionu - jer gdje bi, ako ne u štampariji, bilo mjesto gdje će se do u beskraj prerađivati grafička ploča, matična ploča jednoga sjećanja, koja može biti jednom ili nijednom otisnuta na papir, ili može biti svakodnevno štampana, u vazda različitim varijantama, onako kako to nalažu sjećanja i zaborav. Lijepo je i to zamišljati: grafički listovi koji se svakodnevno štampaju, baš kao dnevne novine, i na kojima izlazi stanje sjećanja jednog umjetnika. To je Borges u Bosni.

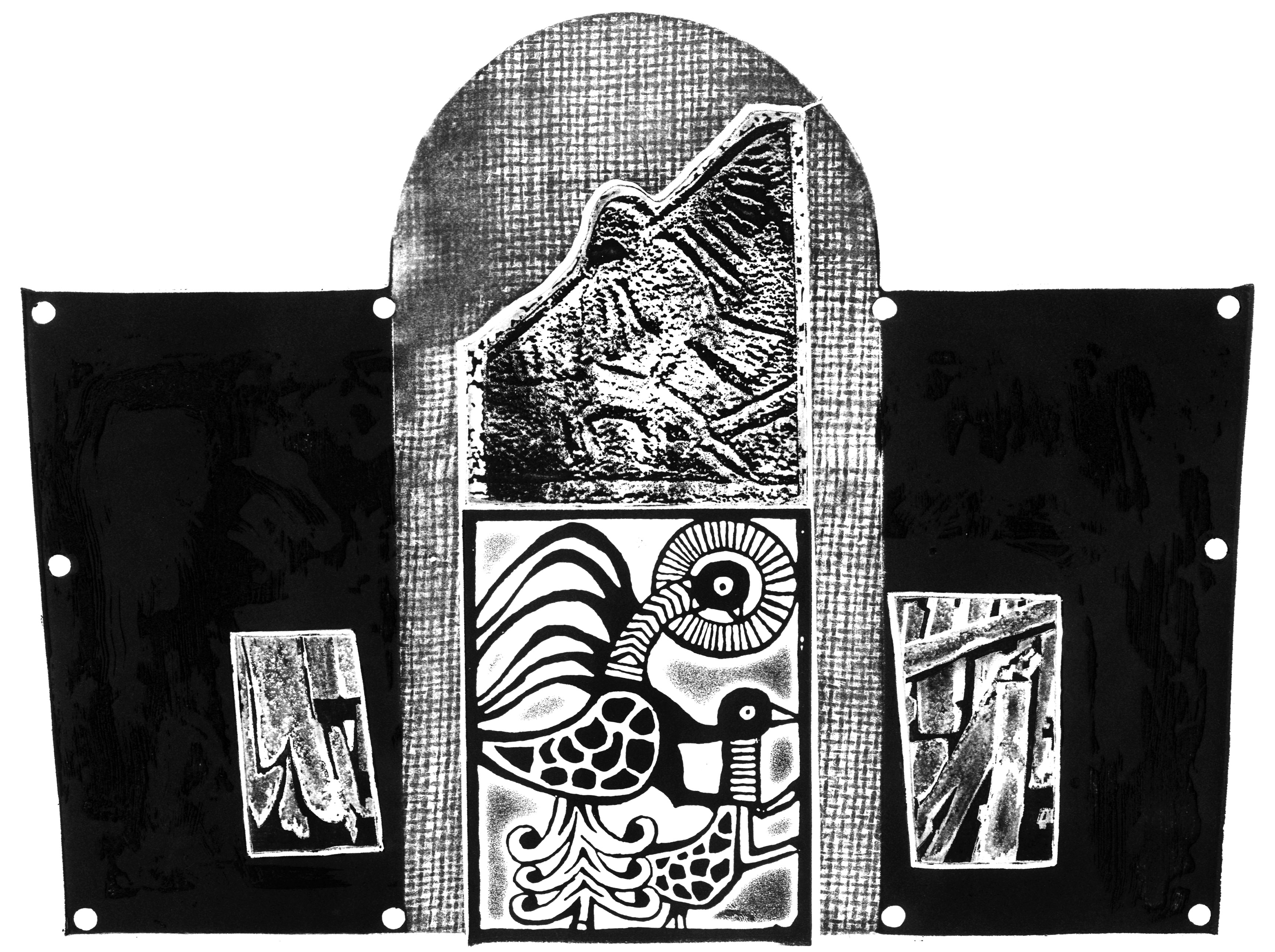

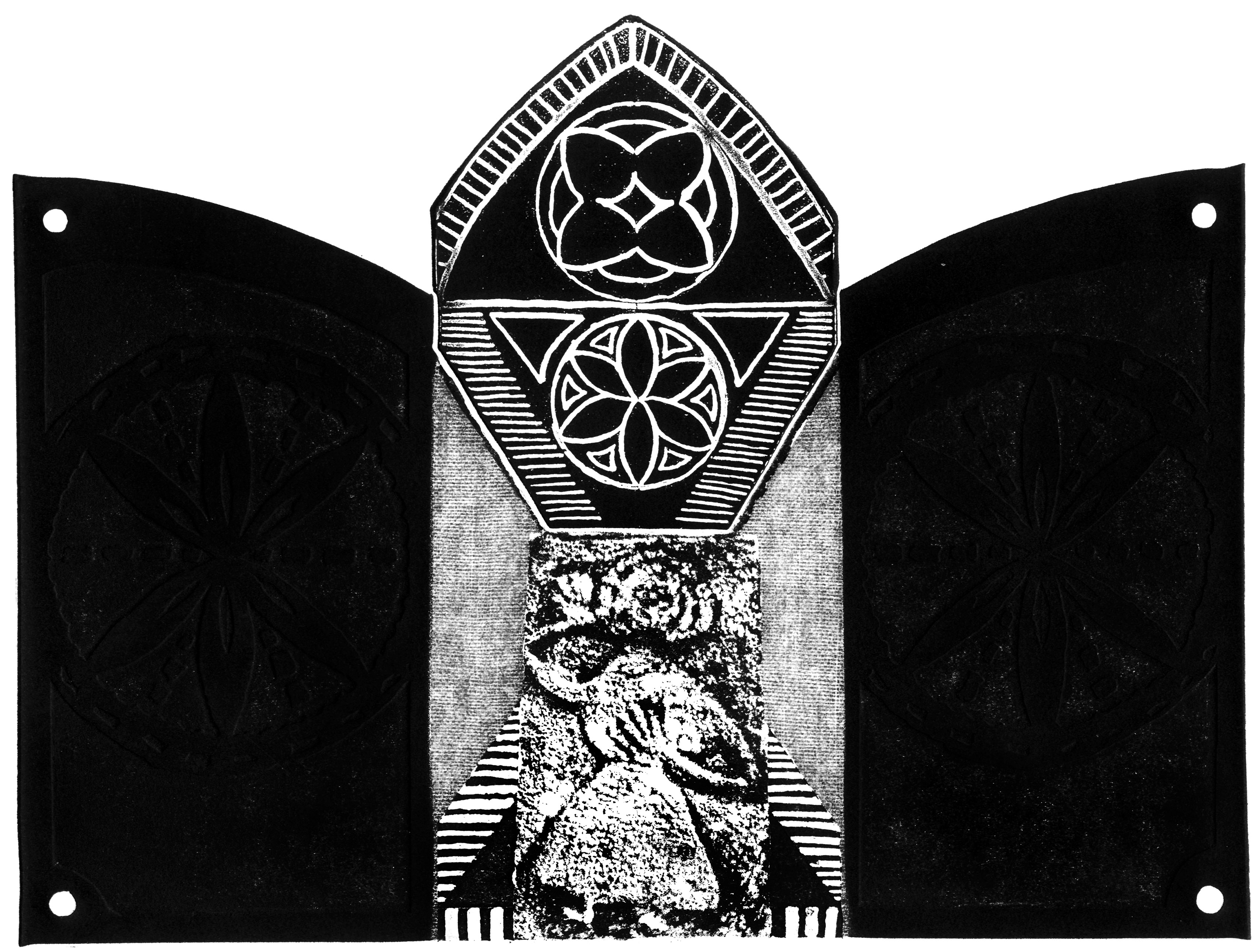

Grafička mapa “XII”, kombinirane tehnike dubokog i visokog tiska, list br. I, 28 x 21 cm

Grafička mapa “XII”, kombinirane tehnike dubokog i visokog tiska, list br. X, 22 x 28 cm

Morine, 2010, 65 cm x 43,5 cm, ciklus fotografija “Mramorovi”

Ravanjska vrata, 2010, 65 cm x 43,5 cm, ciklus fotografija “Mramorovi”

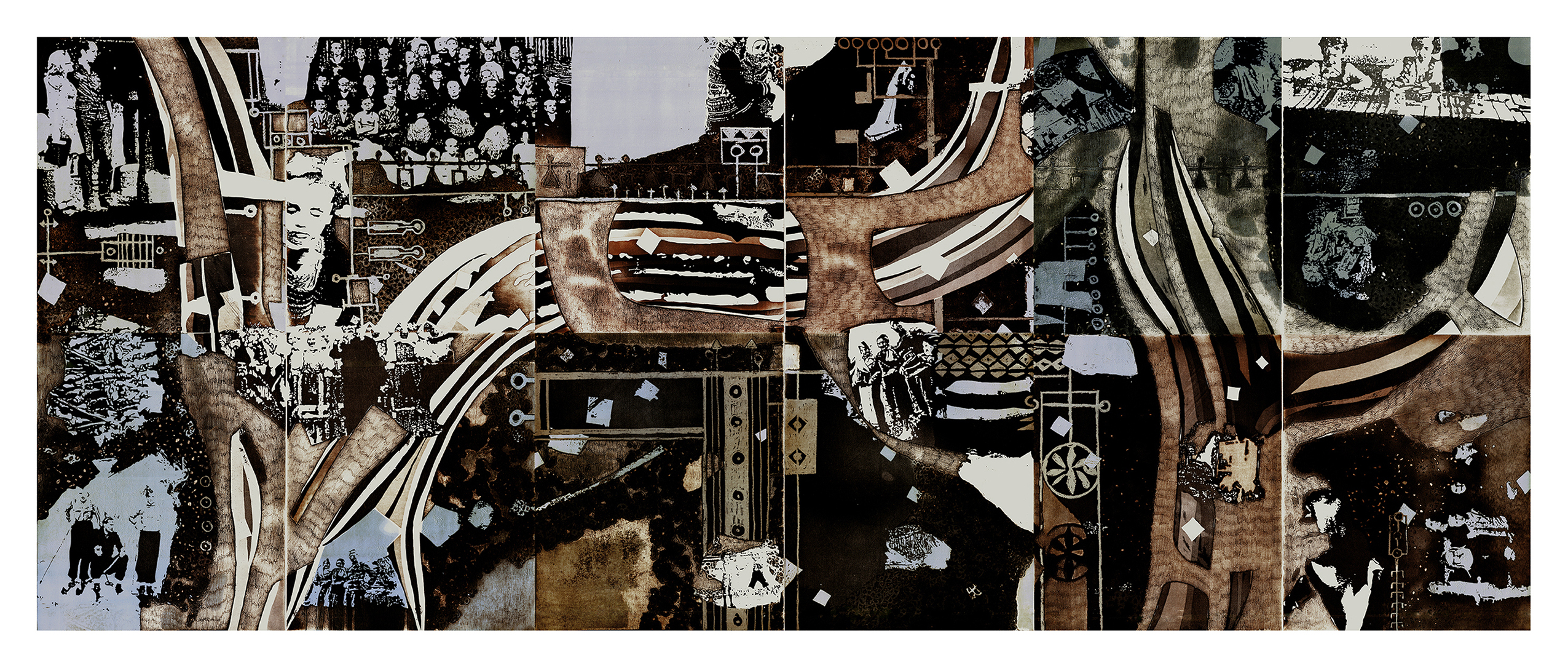

Grafički ciklus “Session”, kombinirane tehnike dubokog i visokog tiska, I, II, III, IV, V, VI, 300 cm x 120 cm

Miljenko Jergović: Josip Lovrenović, The Matrix The topic of everything shown by Josip Lovrenović at this exhibition, in the spring of 2017 in Central Bosnia, is memory. Although, the very same could be said for anyone's exhibition of anything. Everything with a display potential, from the undressed mannequins in the shop window on the main street of Sarajevo in April 1992 to the drawings of Nives Kavurić-Kurtović in the Klovićevi Dvori Gallery in Zagreb in June 2016, plus everything in between – the flowerpots with marigolds in the window of the one-story building, the five-litre jar with sugary water and rose petals on a sunny window of the fifth floor - all of that, at the very moment of their display, turns into memory. You cannot say anything about yourself which has not already turned to memory. Except that there are memories conscious and unconscious, intentional and unintentional. There are wounded memories as well: those are the ones not eaten away by the anarchistic, yet systematic and meaningful power of oblivion, but destroyed by some of the greatest disasters of man and mankind. Two of the largest disasters to memory are war and senility. The latter has a more modern name nowadays: the Alzheimer's disease. The war is the Alzheimer's disease of a civilization. Everything a community remembers once peace has returned is not a memory, but its replacement, a memory surrogate. Post-war times are marked by long and mostly futile attempts to re-establish a memory continuum. This is why writers, painters, directors and actors thrive after the war: so alive, active and prolific. They create fiction that plays the role of memory. Hašek's Good Soldier Švejk, Renoir’s The Grand Illusion, We Were in Auschwitz by Tadeusz Borowski – all of these replaced memories of the victims killed and crazed, but they have also, and perhaps more importantly so, enabled the "post-memorial memories", the memories from beyond the grave. Josip Lovrenović is one of the post-war artists. This should be in his artist's ID, on his card, in the announcement of this exhibition... Although scenes from the front are nowhere to be seen, and there is no mention of the besieged city, mass graves, their genocides and ours, our martyrdom and their butchery or all those post-war trinkets the survivors use to decorate their own empty graves, the war nevertheless takes up the central place in his memory. Or, more precisely, the central gap. This gap is to be filled with very precise - but no less futile - almost forensic attempt at reconstruction of the lost world. In his graduation series of twelve prints in twelve portfolios, Lovrenović used the aquatint technique, with finishes, to transfer the typal scenes and signs from the stećak tombstones, combining them with the objects of everyday use that have lost their purpose in the course of time. It was not a personal memory or the demon of the collective or, God forbid, of the national memory involved - the nation and the memory are the everlasting contradictions - this was the memory of the memory. The stećaks are not reservoirs of the shared memory, or the memory of the world, as national and multinational dreamers would like to put it. They are more likely to be perceived and interpreted as monuments to oblivion. There is no knowledge of who lies beneath them, while their visual, symbolic messages in the course of time and with the power of forgetting have turned from what they once were - very concrete reports on the past life written in everyday language - into the highly stylized visual and textual metaphors. Just as the tools have turned into a kind of metaphor, since nobody knows their purpose any more. The metaphorization through oblivion, or rather the transformation of the real world into metaphors and signs through the process of forgetting – this is a big topic in itself. That is the story of the stećaks, as told by Lovrenović. Years later, in 2005 in Warsaw, during the specialist studies, the series Session was created. Twelve (twelve again!) prints, monumental in format - the largest one technically possible, put together to form one memory unit. The piece uses the family photos saved during the war devastations, persecutions and involuntary migrations by chance, by making up a fragment, visual and substantial, meaningful, within the larger unit of a single print, which again, with the remaining eleven, makes for one even broader, if not the final artistic unit. Session is a fascinating piece since it demonstrates two opposite and opposing principles of creation. At the same time, these are powerful, utterly intimate print miniatures and a sort of a graphic fresco, or rather, the iconostasis. Session is a potential iconostasis of memory. The photos used by Lovrenović in the Session were mostly taken back in the days when the act of photo-taking involved a ceremony of a kind. The future to-be-photographed would line up in front of the lens behind which a photographer stood - a sort of a master of memory, a professional back then, and only after the Second World War a noble dilettante, or, fashionably, an amateur. And in the short exchange of looks, fixing facial expressions, grimaces and gestures, the eternity was caught. Or, more precisely, in the lightning flash of the eternal darkness of the photo strip, the death was recorded. Taking photos is a kind of exercise for the death hour. You will never be the one you are on that photo. And you will never be. The majority of the people from the photos the artist used are unknown him. They are forgotten; they fell out of the memory, turned into anonymous witnesses, the figures and signs from the stećaks. The only ones he knows are those with whom he shares the common generational memory - father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, maybe even great-grandfather, in case anyone in the house still remembered him. All of the human history, family history, and all the history of mankind to a large extent can fit into the memories of three generations: son, father and mother, grandfathers and grandmothers. With the departure of the oldest generation, the entirety of their memory disappears. What remains are only fragments, turned into oral history, legends and myths, empty and unreliable. And so it goes, from one century to another, the history spans between seventy and one hundred and twenty years, which is the length of memories ours and of our loved ones and their memories of memories. Josip Lovrenović captures this process, and captures himself within the process. The family history is his autobiography. In using photos in the printmaking process and without intending so, he recodes them, transforms them and turns them into something else, both visually and in terms of content. What has been a photograph until recently, now becomes a mark on the printing plate, a drawing leaning towards abstraction, and in the end – abstraction and nothingness. This is how the photo once taken crosses the path from a faithful and concrete image of a world to a sign, symbol, and emblem. It is the very same path the symbols and signs from the stećaks have crossed over the centuries. In a very specific sense and a long, long time ago, they were also a photography. The Middle Ages simply did not know about a photography more precise and more accurate than that. And it is just our illusion that something has changed substantially in the period between the stećaks and the images of a digital camera. We are still alone with our memories and with the three generations of memory witnesses, followed by oblivion, wiping of the plate, the void. Session is, in fact, an unfinished piece. The iconostasis of a private memory, of human remembrance, composed of twelve fragments. In Warsaw in 2005 the basis was established, the matrix to be upgraded, modified or deleted infinitely. Potentially, it is a lifelong process, the duration of which is limited solely by the human memory, and then by the relationship of memory and forgetting. Memory will be scratched, written into the printing plate; new elements, faces, shapes and regions will be abraded, and turned into signs and symbols by the act of forgetting. In an attempt to define war trauma, German culturologist and literary historian Aleida Assman summarized a clinical psychology finding from the late twentieth century in the following way: "The memory failing to find a way to the consciousness is written into the body." For the last half a century, maybe even longer, in the world of common people and everyday communication a belief persists that many physical illnesses are caused by psychological trauma, in particular by the war as the trauma of all traumas. But the aphoristically precise conclusion about the body and memory does not necessarily need to refer to a physical illness. The art is, after all, also a trauma written in the flesh and scar tissue, the tumour on the memory and soul. The photos of stećaks are seemingly a more conventional part of this exhibition. In black and white, shot in the style of Tošo Dabac, who had already made a canonized panorama of the world of stećaks some sixty years ago, these photos are a mere "state of affairs". Lovrenović is not involved into belated metaphorization of the stones, he brings them as they are, without inscribing his own experience or the experience of his times into them. He does none of that which is currently fashionable: he does not nationalize the stećaks, does not make them more Bosnian or more international than they themselves are, he does not burden them with his poetic talents nor he reduces them to naively educational world of fairy tales with medieval topics, with the good Bosnian and the land ever noble as central motifs. He shoots them the way they are, free of people and of life, but for the most part free of time that wears them, polishes them and turns them to dust. The role of stećaks in Lovrenović's work is twofold. The repositories of oblivion, the guardians of memory that has belonged to no one for a long time now, the stećaks are now what family photos will become one day. The stećaks are the images of the vanished families. On the other hand, although three-dimensional, the stećak is a kind of printing plate. Into it, it was carved, scratched, inscribed, that which could one day be printed on paper, by the power of an almighty heavenly printer, in the printing house for all formats. Lovrenović is not the one who discovered it, graphic artists before him had known it as well: the stećak is the primary source of the multioriginal art. The face of the stećak longs to be printed. The place of this exhibition is good, and accurate. It is truthful. In addition to Dolac and Travnik as the mythical places of the Bosnian story, the Bosnian art and historic narratives, the Machine factory and printing house carry the meaning and the symbolism equally close to Lovrenović's strategy of remembrance and to his endless and lifelong Session. Because is there really a better place than the printing house to endlessly work on the printing plate, the matrix of a memory which can and does not have to be printed on paper, or it can be printed every day, always in different variations, following the dictate of memory and forgetting. It is a nice thing to imagine, really: prints coming out every day, just like a newspaper, delivering daily the state of the memories of an artist. Borges in Bosnia, that is what it is. (Translation into English: Anda Bukvić Pažin) Miljenko Jergović: Josip Lovrenović, Festplatte Alles, was Josip Lovrenović im Rahmen dieser Ausstellung im Frühjahr 2017 zeigt, handelt von der Erinnerung. Das allerdings kann man über jede Ausstellung sagen, wer auch immer sie ausrichtet und was auch immer ausgestellt wird. Jedes Ausstellungsobjekt, von den entkleideten Schaufensterpuppen einer Hauptstrasse in Sarajewo im Jahre 1992 bis zu den Zeichnungen von Nives Kavurić-Kurtović in der Galerie Klovićevi dvori in Zagreb im Juni 2016 und alles, was zwischen diesen beiden Ausstellungen liegt, Blumentöpfe mit türkischen Nelken im Fenster eines einstöckigen Hauses, Fünfliter-Behälter mit gezuckertem Wasser und Rosenblättern im sonnenbeschienenen Fenster einer fünften Etage, all das ist im Augenblick seiner Ausstellung schon Erinnerung. Der Mensch kann nichts über sich sagen, was nicht schon Erinnerung wäre. Jedoch gibt es bewusste und unbewusste Erinnerungen, absichtliche und unabsichtliche. Es gibt auch beschädigte Erinnerungen: das sind jene Erinnerungen, die von einer, wenn nicht anarchoiden, so doch wesentlichen und sinnhaften Kraft des Vergessens verschluckt wurden, jene, die bei große Notsituationen einzelner Menschen oder der ganzen Menschheit zu Schaden kommen. Krieg und Senilität sind die beiden größten Notsituationen. Letztere hat heutzutage einen modernen Namen: die Alzheimer-Krankheit. Krieg ist die Alzheimer-Krankheit einer ganzen Zivilisation. Das, woran sich eine Gemeinschaft erinnert, wenn Frieden einkehrt, ist nicht Erinnerung, sondern ihr Ersatz, ein Surrogat für Erinnerung. Nachkriegszeiten sind von langen und vergeblichen Versuchen gekennzeichnet, die Kontinuität der Erinnerung wiederherzustellen. Deshalb sind Schriftsteller, bildende Künstler, Regisseure und Schauspieler in Nachkriegszeiten auch so besonders lebendig, aktiv und produktiv. Sie schaffen die Fiktion, die die Rolle einer Erinnerung spielen soll. Hašeks Braver Soldat Schwejk, Renoirs Grande Illusion, Tadeusz Borowskis Bei uns in Auschwitz ersetzten die Erinnerungen der Generationen von Verunglückten und Verrücktgewordenen, haben aber - was möglicherweise noch wichtiger ist - eine „postmemorierende Erinnerung“ über die Gräber hinaus erst möglich gemacht. Josip Lovrenović ist ein Nachkriegskünstler. Genau so müsste es in seiner Künstlerlegitimation stehen, auf seiner Visitenkarte, auf Ausstellungsplakaten... Auch wenn da nirgends Bilder von der Front zu sehen sind, keine belagerten Städte, keine Massengräber ihrer oder unserer Massenmorde, weder ihr Märtyrertum noch unser Verschulden, kein Nachkriegs-Tand, mit dem Überlebende ihre leeren Gräber schmücken, und dennoch ist der Krieg zentraler Ort seiner Erinnerung. Oder genauer gesagt: zentrale Leere. Diese Leere gilt es mit einem sehr präzisen – dadurch nicht weniger vergeblichen -, ja, geradezu forensischen Rekonstruktionsversuch einer verlorenen Welt aufzufüllen. In seinem grafischen Diplom-Zyklus, bestehend aus zwölf Blättern in zwölf Mappen, hat Lovrenović mit einer Wassertintentechnik, neben anderen Ergänzungstechniken, Typenbilder und –zeichen von Stećak-Grabsteinen übertragen und sie mit Alltagsgegenständen, deren Zweck im Laufe der Zeit verloren gegangen ist, kombiniert. Dabei handelt es sich nicht um persönliche Erinnerung, ebenso wenig um den bösen Geist einer kollektiven oder gar, Gott bewahre!, nationalen Erinnerung – Nation und Erinnerung stehen in ewigem Widerspruch -, sondern um die Erinnerung einer Erinnerung. Stećak-Grabsteine sind als Behältnisse für gemeinsame Erinnerungen ungeeignet, oder für Welterinnerung, wie es nationale oder multinationale Phantasten gerne ausdrücken würden. Eher könnte man sie als Deuter von Vergessensdenkmälern bezeichnen. Wer unter ihnen liegt, ist nicht mehr bekannt, und die visuellen, symbolischen Mitteilungen auf ihnen haben sich im Laufe der Zeit und kraft des Vergessens von sehr konkreten, alltagssprachlichen Zeugnissen eines vergangenen Lebens zu hochstilisierten, visuellen und textuellen Metaphern gewandelt. Ebenso haben sich die Werkzeuge, von denen niemand mehr weiß, wofür man sie gebrauchen kann, zu eigentümlichen Metaphern entwickelt. Eine Metaphorisierung durch das Vergessen oder die Verwandlung einer wirklichen Welt zu einer Metapher bzw. einem Zeichen im Prozess des Vergessens, schon das allein wäre ein großes Thema. Darin enthalten ist auch die Geschichte der Stećak-Grabsteine, so wie Lovrenović sie präsentiert. Viele Jahre später, während seiner Studienjahre, in denen er sich in Warschau weiterbildet, entsteht der Zyklus Session. Zwölf (schon wieder zwölf) Grafikblätter monumentalen Formats - dem größten, das technisch herstellbar war – fügen sich zu einem Erinnerungs-Ganzen. Bei der Arbeit wurden Familienbilder benutzt, die von der Kriegsverwüstung, von Verfolgung und unfreiwilliger Umsiedelung verschont geblieben waren, und die ein visuelles, inhaltliches und bedeutungsgeladenes Fragment in der Gesamtheit eines Grafikblatts ausmachen, das wiederum zusammen mit den restlichen elf Blättern eine noch größere, wenngleich nicht endgültige, Ganzheit der Arbeit darstellen. Session ist ein eindrucksvolles Werk, denn es demonstriert zwei widersprüchliche und gegeneinander gesetzte Schaffensprinzipien. Gleichzeitig handelt es sich um kraftvolle, vollkommen intime graphische Miniaturen, um eine Art graphisches Fresko oder, besser gesagt, eine Ikonostase. Session ist eine mögliche Ikonostase der Erinnerung. Die Fotografien, die Lovrenović in Session verwendet hat, kommen aus einer Zeit, in der der Akt des Fotografierens eine Art Zeremonie war. Die zu Fotografierenden postierten sich vor dem Objektiv, hinter dem der Fotograf stand – sozusagen der Herr der Erinnerung -, der Profi, erst nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg ein edler Dilettant – moderner gesagt, ein Amateur -, der in kurzer Abfolge Ansichten, Gesichtsausdrücke, Grimassen und Gesten für die Ewigkeit einfing. Oder, genauer gesagt, im blitzartigen Aufhellen der ewigen Finsternis des Fotofilms den Tod einfing. Die Fotografie ist eine Art Einübung des Todesmoments. Auf diesem Bild bist du einer, der du nie wieder sein wirst. Und etwas, das du nie wieder sein wirst. Die meisten Menschen der verwendeten Fotografien kennt der Künstler nicht. Sie sind vergessen, aus der Erinnerung gefallen, zu anonymen Zeugen geworden, zu Figuren und Zeichen der Stećak-Steine. Bekannt sind ihm nur jene, mit denen er eine Generationserinnerung teilt – der Vater also, die Mutter, der Großvater, die Großmutter, vielleicht noch der Urgroßvater, falls sich im Haus noch jemand an den Urgroßvater erinnert. Jede Menschenerinnerung, jede Familienerinnerung, meist auch die ganze Erinnerung der Menschheit passt in die Erinnerung dreier Generationen: die des Sohnes, des Vaters und der Mutter, der Großmutter und des Großvaters. Mit dem Fortgang der ältesten Generation verblasst ihre gesamte Erinnerung. Es bleiben nur Fragmente, die in Überlieferung, Legende und Mythos verwandelt werden, unzuverlässig und leer. Auf diese Weise umfasst die Geschichte von Jahrhundert zu Jahrhundert ungefähr siebzig bis hundertzwanzig Jahre, solange eben, wie unsere Erinnerungen und die unserer nächsten Verwandten eben dauern, und ihre Erinnerungen an die Erinnerungen. Josip Lovrenović zeichnet diesen Prozess und sich selbst innerhalb dieses Prozesses auf. Die Familiengeschichte ist seine Autobiografie. Indem er die Fotografien im grafischen Prozess einsetzt, rekodiert er sie ohne Absicht, verwandelt sie und macht etwas anderes daraus, visuell wie auch inhaltlich. Was eben noch Fotografie war, ist nun eine Spur auf der Grafikplatte, eine Zeichnung, die nach Abstraktion strebt und schließlich – Abstraktion und nichts weiter. So unternimmt das einmal aufgenommene Bild eine Reise vom getreuen und konkreten Bild einer Welt zum Zeichen, Symbol, Emblem. Dabei geht es um denselben Weg, den durch das Jahrhundert hindurch auch die Stećak-Steine genommen haben. Auch sie sind in gewissem Sinn einmal das gewesen - Fotografien. Genauere und wahrhaftigere Fotografien gab es im Mittelalter ja nicht. Und wir leben in der Illusion, es habe sich von den Stećak-Steinen bis zu den digitalen Bildern etwas Wesentliches verändert. Wir sind mit unseren Erinnerungen immer noch alleine und mit drei Generationen erinnernder Zeugen, nach welchen das Vergessen kommt, das Löschen der Festplatte, die Leere. Session ist eigentlich eine unvollendete Arbeit. Die Ikonostase einer persönlichen Erinnerung, einer Menschenerinnerung, komponiert aus zwölf Fragmenten. In Warschau im Jahre 2005 wurde der Grundstein gesetzt, eine Festplatte erstellt, die endlos ausgebaut, verändert und gelöscht werden kann. Dabei geht es potentiell um einen ein ganzes Leben umfassenden Prozess, dessen Dauer auf die menschliche Erinnerung beschränkt ist und darüber hinaus auf das Verhältnis von Erinnern und Vergessen. Die Erinnerung wird auf dieser Graphikplatte neue Elemente, Gesichter, Formen und Gelände einritzen, einschreiben, ja einfressen, und diese werden sich mit dem Fortschreiten des Vergessens in Zeichen und Symbole verwandeln. Beim Versuch, das Kriegstrauma zu definieren, liefert Aleida Assmann, die deutsche Kulturwissenschaftlerin und Kunsthistorikerin, folgende psychologische Diagnose für das Ende des Zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts: „Erinnerung, die nicht den Weg ins Bewusstsein findet, schreibt sich in den Körper ein.“ In der letzten Hälfte des Jahrhunderts, vielleicht sogar länger, hat sich in der Alltagskommunikation der Menschen der Glaube breitgemacht, dass viele physischen Krankheiten durch psychische Traumata ausgelöst werden, und durch Krieg, dem größten Trauma aller Traumata. Allerdings muss diese aphoristisch präzise Schlussfolgerung über den Körper und die Erinnerung nicht unbedingt auf körperliche Krankheiten angewendet werden. Auch die Kunst ist letztendlich ein Trauma, das sich in den Körper einschreibt, wildwucherndes Fleisch, ein Tumor der Seele und des Gedächtnisses. Die Fotografien der Stećak-Steine machen den scheinbar konventionellen Teil der Ausstellung aus. Diese Fotografien stellen in ihrer Schwarz-Weiss-Technik, aufgenommen im Stile eines Tošo Dabac, der schon vor rund sechzig Jahren ein kanonisiertes Panorama der Stećak-Steine schuf, sozusagen den nackten „Stand der Dinge“ dar. Lovrenović befasst sich nicht mit der rückwirkenden Metaphorisierung seiner Steine, er zeigt sie so, wie sie sind, schreibt auch seine eigene Erfahrung nicht in sie ein, ebenso wenig wie die Erfahrung seiner Epoche. Er tut nichts von all dem, was heute so in Mode ist, er nationalisiert die Stećak-Steine nicht, er behauptet nicht, sie seien bosnisch oder welteigen, sondern eben nur das, was sie allein durch sich selbst sind. Er drängt ihnen keine eigene poetische Note auf, bringt sie nicht mit der naiv-gelehrten Welt der Märchen und mit mittelalterlichen Themen in Verbindung, nicht mit den guten Bosniaken und deren edlem Land als Hauptmotiv. Er fotografiert sie so, wie sie sind, frei von Menschen und Leben, und vor allem frei von der Zeit, die sie abnutzt, glättet und in Staub zerfallen lässt. Die Stećak-Steine in Lovrenovićs Arbeit haben eine doppelte Funktion. Als Vergessens-Depot, als Hüter eines Gedächtnisses, das längst niemandem mehr gehört, sind Stećak-Steine das, was einmal Familienfotografien sein würden. Stećak-Steine sind Bilder von verstorbenen Familien. Andererseits, obgleich dreidimensional, ist der Stećak eine Art graphische Festplatte. In sie wurde eingraviert, eingeritzt, eingeschrieben, was ein allmächtiger himmlischer Druckmeister eines Tages in einer Druckerei für alle Formate auf Papier drucken könnte. Das hat Lovrenović nicht neu entdeckt, das haben andere Grafiker vor ihm schon gewusst, denn der Stećak ist der Urbeginn einer Kunst des Multi-Originals. Das Antlitz eines Stećaks ist dafür vorgesehen, vervielfältigt zu werden. Diese Ausstellung hat einen passenden und genauen Ort. Einen wahrhaften Ort. Abgesehen davon, dass Dolac und Travnik mythische Orte innerhalb der bosnischen Geschichte sind, innerhalb der bosnischen Narration, eines künstlerischen wie auch historischen, trägt auch die Maschinenfabrik und Druckerei selbst eine Bedeutung und Symbolik in sich, die Lovrenovićs Erinnerungsstrategie und seinen endlosen und lebenslangen Sessions sehr nahe kommt – denn an welchen Ort könnte sie besser passen, wenn nicht in eine Druckerei, wo könnte diese in alle Ewigkeit arbeitende Grafikplatte, diese Festplatte einer Erinnerung, die einmal oder nie auf Papier abgedruckt werden kann, oder täglich in immer neuen Varianten vervielfältigt werden kann, genau so, wie Erinnerung und Vergessen dies immer wieder tun. Was für eine schöne Vorstellung: Grafikblätter, die täglich wie Tageszeitungen gedruckt werden und aus denen der momentane Zustand eines Künstlers spricht. Ein Borges in Bosnien. (Übersetzung ins Deutsche: Anne-Kathrin Godec)